This exhibition by artist Anna Dumitriu explores the strange histories and emerging futures of dentistry from teeth worms, false teeth and the development of anaesthetics to 3D printing and the DNA of dental microbes. It looks at the societal and psychological impacts of this defining field of medicine through a deep investigation of the Birmingham Dental Hospital Historic Collection and collaboration with present day researchers who work at the cutting edge of medical science.

Opening event with refreshments: 5pm on 3rd October 2019 meet the artist and curator

Exhibition open from 4th October 2019 – 17th January 2020 during Birmingham Dental Hospital opening hours.

Free drop in Teeth Marks workshop exploring the techniques used in the exhibition and making your own artworks with Anna Dumitriu and Dr Melissa Grant at Birmingham Dental Hospital 12.30pm – 4.30pm

Artist’s talk at the Barber Institute of Art on 20th November 2019. Anna Dumitriu will discuss her artistic practice and the Teeth Marks project followed by a discussion with Dr Melissa Grant with audience questions. This event is in collaboration with the Barber Association.

A key inspiration behind the project is the powerful relationship between dentistry and jewellery-making. The first BDH was built in 1858 and was the first in the UK. Its original location was in Temple Street on the edge of the world-famous Birmingham Jewellery Quarter so it could to take advantage of the expertise of the silver and goldsmiths there. This story is explored in Talisman which references both the historical relationship of dentistry and jewellery-making, as well as the future directions of both fields, using 3D scanning and 3D printing in the form of a charm bracelet based on photogrammetry scans of the BDH collection.

The Most Profound Mystery investigates how fans were used historically to hide the stigma of rotten teeth and foul breath. Dumitriu has altered an antique bone fan repairing it with gold wire and silk patterned with bacteria that cause gum disease. Historically false teeth were made either from carved bone or ivory and sometimes incorporated human teeth. These were often wired in over infected gums like Mausoleums of Gold Over a Mass of Sepsis. For a brief period, in the 19th Century doctors began to believe that bad teeth were to blame for almost any illness that they had struggled to diagnose, which led to unnecessary mass extractions and the accompanying psychological and physical pain. There are some echoes here of our contemporary fascination for the human microbiome which has been linked to obesity and depression, though research is not fully conclusive many people are profiting from products sold in this belief.

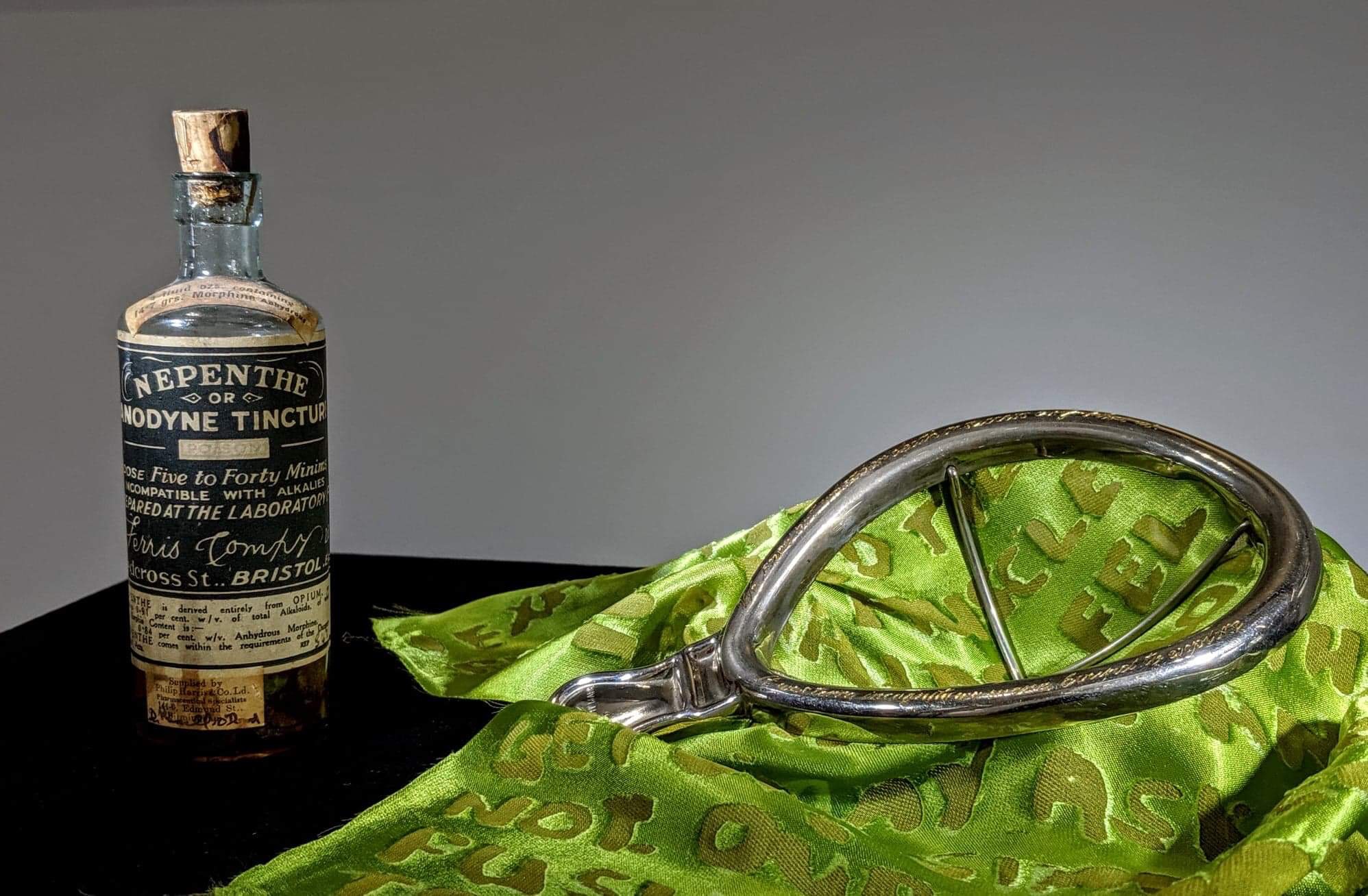

Terra Incognita We Were Bound to Explore references the desire for painless dental surgery and the development of anaesthetics, as well as the surprising protests against these early discoveries by those who saw suffering as a virtue. Many of the pioneers of anaesthetics misused their own discoveries and, in some cases, became addicted to them through the process of self-experimentation, leading to shocking outcomes. We can see parallels with our modern desire for a pain free existence and the resulting opioid crisis in some parts of the world that has resulted from the over promotion of addictive prescription medications and a subsequent black market. The goal of removing pain is a complex ethical area and an ongoing field of research.

Pioneers in the stranger than fiction history of dentistry helped to define the field of modern surgery, and dental researchers today continue to develop innovations we will see in the future. This exhibition draws threads across time and asks us to consider where the potential benefits, and risks, might occur.

The Most Profound Mystery

In his 1845 essay ‘On Artificial Teeth’ W.H. Mortimer described false teeth as “the most profound mystery” because they were never discussed, instead people would hide their bad teeth and foul breath using fans. This altered antique fan is made from animal bone and has been mended with gold-plated wire. The silk of the fan and ribbon has been grown and patterned with two species of oral pathogens Prevotella intermedia and Porphyromonas gingivalis (the cloth having been embedded in the bacteria on agar plates and in liquid media and then sterilised). These bacteria cause gum disease and bad breath, and the latter has also recently been linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

Talisman

A talisman was traditionally believed to protect its wearer from harm, and the idea of the charm bracelet evolved from it. The charm bracelet became a popular product for Birmingham Jewellery Quarter and this bracelet references both the historical relationship of dentistry and jewellery-making, and the future directions of both fields: 3D scanning and 3D printing. The charms are based on photogrammetry scans of important pieces from the Birmingham Dental Hospital collection: a narwhal tusk (a symbol of dentistry), a dental key (for extracting teeth), a pelican (for extracting teeth), pliers for (extracting teeth), a device for opening locked jaws, an impressions plate, a dental bridge with human teeth, false teeth carved from animal bone, a device for gouging out teeth, and a tooth from an Anglo Saxon archaeological site which has been ground flat by a gritty diet. Some of those original artefacts surround the bracelet.

Relic

The DNA of an organism contains the instruction book of how that organism is made. Today we are able to read and compare the DNA of bacteria to learn more about them, how they are transmitted and how they can be treated. Inside this sealed box is the DNA of Porphyromonas gingivalis, an important dental bacterium which can cause serious gum disease and has also recently been linked to Alzheimer’s disease. This DNA is a relic of the scientific research taking place at Birmingham Dental Hospital nowadays.

Teeth Worms

In ancient times people believed that tooth decay was due to tiny worms living in the teeth and eating away at them from within. This may have been because tooth pulp squeezing out of a broken tooth resembles a worm. Beeswax was used sometimes used for fillings in broken teeth in early dentistry but of course it was not very effective or strong.

Mausoleums of Gold

Around the turn of the 20th Century so-called “American Dentistry” had become known as the state of the art in the field, this involved expensive restoration work where well-constructed bridges were attached over broken and rotten roots. This seems bizarre nowadays but in the early days of microbiology it was not known that bacterial infections could travel from the mouth into other parts of the body. In 1911 Dr William Hunter of London had several poorly patients with various conditions he could not diagnose but he noticed they had “American Dentistry” work and unhealthy mouths. He persuaded a few of the patients to remove the costly bridges and treat the affected roots. Those patients soon recovered and Hunter presented his observations in a paper at a medical conference in Montreal, where he described the bridges as “mausoleums of gold over a bed of sepsis”. Doctors realised that infections in the mouth could also travel to other parts of the body but they incorrectly began to attribute almost any illness they struggled to diagnose to bad teeth and whatever the symptoms they decided to extract the teeth. A cautionary tale for modern medicine.

Terra Incognita

This piece explores the tragic story of Horace Wells, a sensitive sole who hated to cause pain and found his chosen profession of dentistry (in pre-anaesthesia days) extremely disturbing. He would sometimes have to take weeks off after a difficult surgery to recover from his torment and once gave the job up altogether. He discovered anaesthesia by inhalation in 1844 following a trip to an entertainment show of the effects of ‘laughing gas’ (nitrous oxide) where the effects of the gas caused Well’s friend to stumble and cut his leg badly but said he had felt no pain at all. Wells hit on the idea and the very next day Wells had a dentist friend called John M. Riggs extract one of his teeth while under the influence of nitrous oxide. In Riggs’ own words:

“Wells took his seat in the operating chair. I examined the tooth so as to be ready to operate without delay. Wells took the bag [of nitrous oxide] in his lap-held the tube to his mouth & inhaled till insensibility relaxed the muscles of his arms, his hands fell on his breast-his head dropped on the head-rest & I instantly, passed the forceps into the mouth-onto the tooth and extracted it…We knew not whether death or success confronted us. It was terra incognito we were bound to explore-the result is known to the world.”

Wells continued to self-experiment ways of removing pain and became addicted to chloroform, leading to a tragic series of events.

Anna Dumitriu Biography

Anna Dumitriu is a British artist who works with BioArt, sculpture, installation, and digital media to explore our relationship to infectious diseases, synthetic biology and robotics. She has an extensive international exhibition profile including ZKM, Ars Electronica Festival, BOZAR, The 6th Guangzhou Triennial, The Picasso Museum, Philadelphia Science Center, The Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei, LABoral, Art Laboratory Berlin, The History of Science Museum Oxford, Furtherfield London and HeK Basel. She was the 2018 President of the Science and the Arts Section of the British Science Association. Her work is held in public collections including the Science Museum London and Eden Project. She is Artist in Residence on the Modernising Medical Microbiology Project at The University of Oxford and with the National Collection of Type Cultures at Public Health England.

The exhibition was generously supported by Arts Council England